The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias

Status Quo Bias

People display inertia in various contexts. For example, they tend to stick to a certain habit or belief unless some external force compels them to change their behavior. Since humans generally have a preference for stability, this is not surprising. However, in some situations, we observe a tendency to maintain the status quo even when there may be better alternatives out there (or when there is simply no reason to keep things as they are). Here is some evidence for status quo bias, using some examples from a 1988 paper by William Samuelson and Richard Zeckhauser, who coined this term.

A group of participants saw the following question (neutral version):

Having just completed your graduate degree, you have three offers of teaching jobs in hand. Your choices are (select one):

College A: midwest, low prestige school, moderate salary, very good chance of tenure

College B: west coast, low prestige school, high salary, good chance of tenure

College C: east coast, high prestige school, high salary, fair chance of tenure

Others saw a version where one of the options was made the default. For example:

You are currently an assistant professor at College C in the east coast. Recently, you have been approached by colleagues at other universities with job opportunities. Your choices are (select one):

College A: midwest, low prestige school, moderate salary, very good chance of tenure

College B: west coast, low prestige school, high salary, good chance of tenure

Remain at College C: east coast, high prestige school, high salary, fair chance of tenure

In the neutral version, 11 out of 35 subjects selected College C. However, in the version where College C was designated as the status quo, it was selected by 31 out of 42 subjects!

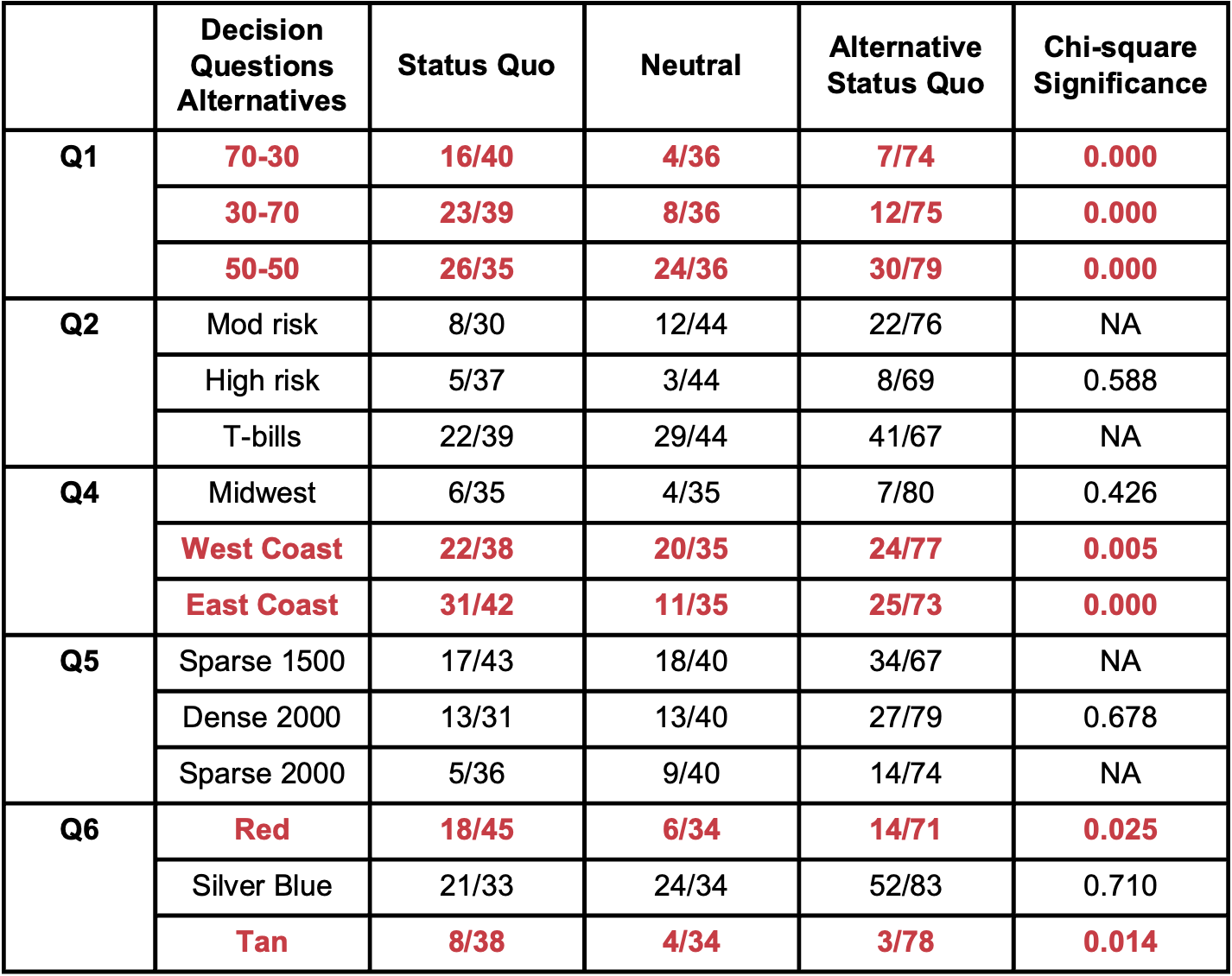

In several examples in the paper, as well as our replication, an option made the status quo became significantly more popular as the final choice. Below is a summary of our results.